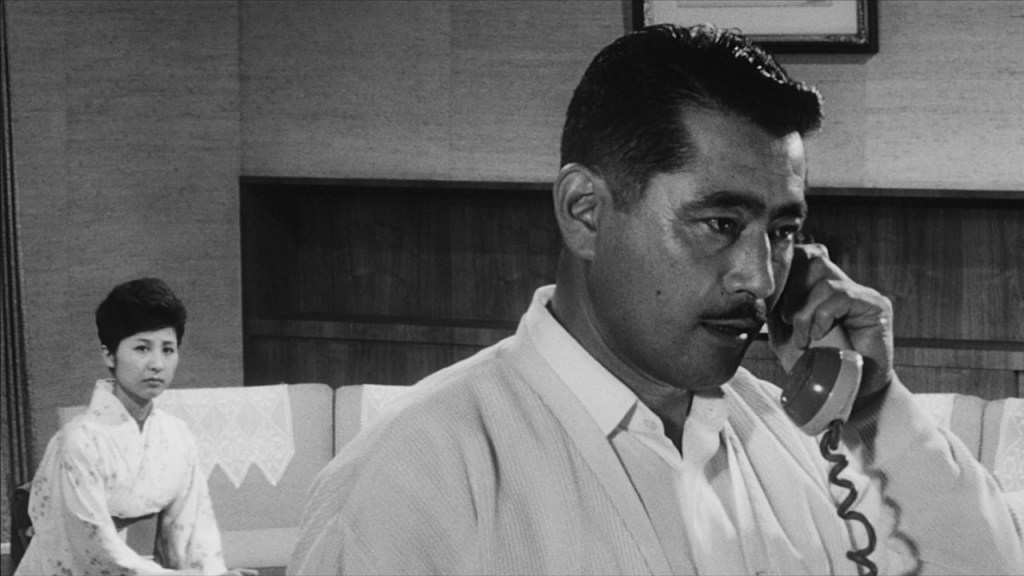

This weekend’s double feature was an incredible, undoubtable success: Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963) and its brand new reimagining: Spike Lee’s Highest 2 Lowest (2025). First things first: Kurosawa’s film is a classic for a reason. From the very first scene, I was entranced by the lighting, blocking and staging. The amazing shots don’t stop, and the plot’s tension builds and crests repeatedly and masterfully over the 143-minute runtime. The film stars Toshirô Mifune as Gondo the wealthy protagonist, Kyôko Kagawa as his wife Reiko, Tatsuya Nakadai as Police Inspector Tokura, and Tsutomu Yamazaki as the kidnapper. The acting is strong though a bit soapy through today’s eyes, as is to be expected for its era. Spike Lee had a challenging flight plan to follow, and I’d argue he successfully lands the plane.

Highest 2 Lowest has a stacked cast from film stars Denzel Washington and Jeffrey Wright to screen new(er) comers A$AP Rocky, Aubrey Joseph, Ice Spice, and Princess Nokia. I’m just as surprised as you to share that everyone on the cast was solid; the film isn’t marred by a single bad performance. Film construction wise, Lee takes a different approach from the original: whereas the standout element of Kurosawa’s film is the blocking and striking shots, Lee uses clever framing of striking sets and repetition of scenes from multiple perspectives to catch the audience’s eyes. Plenty of small touches create a full viewing experience: from the classic Spike Lee reverence of NYC shining through to the realistic cultural references such as Muhammad Ali and Stevie Wonder on the walls of a Black home. Still, Lee stays relatively true to the original film’s plot.

Rather than significant plot changes, Lee revives the story with key alterations that highlight a modern, American cultural context. Below I detail five major changes made in Spike Lee’s adaptation of Akira Kurosawa’s classic film.

Spoilers ahead!

More Than the Help

Both films begin with the same incredible setup, based loosely on the 1959 novel King’s Ransom by Evan Hunter: a wealthy man has to decide whether or not to pay the ransom when his chauffeur’s son is mistakenly kidnapped in place of the his own, and at the risk of personal financial ruin. It’s a wild premise circling a moral conundrum: how much would you sacrifice for another’s child? One of Lee’s first interesting plot changes is the nature of the relationship between the wealthy man and his chauffeur: in Kurosawa’s version the two seem to have no personal relationship despite their children being playmates, however in the remake, David King, portrayed by Washington and his chauffeur Paul Christopher, portrayed by Wright, are close friends. Paul is familiar with the details of David’s financial dealings and also has his own office in the King’s home. Lee’s choice to tighten the men’s relationship heightens the stakes of the situation: in addition to the moral and financial conundrum, there is also an emotional one as David weighs the life of his son’s best friend whose father is one of his own.

Both Washington and Wright, both lauded actors in their own rights, are stellar as friends facing an impossible situation together. Not only do we see Paul serve as a supportive figure in David’s life before the kidnapping, but we also see the two collaborate as buddy vigilantes in the film’s conclusion. Lee brings the power of friendship into play as an inherently positive force, highlighting a moral lesson absent from the original film.

A Family Decision vs. One Man’s

Speaking of friendship, another key difference in Lee’s adaptation is the role of David’s son, Trey, portrayed by Aubrey Joseph, who adamantly advocates for his friend’s life. In the original film, Gondo’s son is around 9 years old and speaks only briefly. In Lee’s adaptation, Trey pleads with his father so vigorously that they have a brief altercation about the language Trey uses. Lee chooses to highlight again the moral goodness of loyal friendship.

In addition to his child, David turns to his wife for counsel about the decision to pay the ransom which is a huge departure from the original in which Gondo berates and dismisses his wife’s pleas for him to pay. Gondo insists that his wife, Reiko, is too ignorant to understand the choice being faced and too naive to the scope of the probable ripples on their lives. While Gondo’s treatment of his wife reads misogynistic and cruel when viewed in the light of 2025, it feels representative of gender politics of the era. In any case, Lee’s protagonist thankfully has an improved view on marriage, partnership and women, intentionally turning toward his wife, Pam, for perspective. Bringing her into the decision with a poignant, intimate dialogue held just between the two. And while Pam ultimately defers to her husband’s decision, she offers a measured and realistic position which sits in opposition to Reiko whose perspective appears to be a purely emotional one: the mother pleading for the life of a child. While there is of course nothing wrong with having an emotional response to a heightened situation or with emotional women, there is something wrong with a flat portrayal of women as irrational. When faced with the real financial implications of paying the ransom, Reiko is silent and offers no additional rebuttal or ideas. In contrast, Pam is the one to name the financial stakes the family is facing, demonstrating an ability to hold both logic and emotion with maturity even when they seemingly conflict. Lee offers a humanizing and feminist reimagining of women in his film.

One of the best scenes in the movie is when the King family unifies in their decision to pay the ransom. As opposed to Kurosawa’s film wherein the decision is totally Gondo’s and his individual turmoil is prioritized and taken seriously, in Lee’s film the family is a united front. Informing the police together of their decision and sitting together while preparing the ransom for delivery. It is a powerful moment highlighting not only a shared responsibility but also the strength of the King family unit. The decision is not just about the moral fiber of David but about the family unit he has cultivated in partnership with his wife and child.

Violent Vigilantism Saves the Day Not Cops

Kurosawa’s classic is rightfully praised for its grand transition in act two to a fast-paced, intricate crime drama. We spend the last hour and change of the original film following the dedicated police force of Yokohama as they diligently make use of excellent research, interviews and observation to successfully identify and capture the kidnapper as well as recover most of the ransom money. In the original film: Gondo is the hero of the first act, and the police force is the hero of the second act. Not so in Lee’s adaptation.

We witness early hints of the police’s ineptitude when they first encounter Paul, a former criminal who served his time and has obviously turned his life around with faith and industriousness. Despite the audience’s knowledge of Paul as a righteous man and a good father, the police immediately harass and denigrate him for his past. It is a moral failing to believe that a man who has served his time cannot change his life, and it is outright upsetting to watch a man whose child is missing be treated with the mean-spirited nastiness that the officers do. (Fun fact: Wright’s son in the movie, Kyle, is portrayed by his actual son, Elijah Wright!) Next, we watch Inspector Higgins, portrayed by Dean Winters of Allstate Mayhem commercial fame, struggle to chase down the kidnappers on the run with the ransom funds and ultimately fail to keep his eyes on the correct package throughout, leading to an exciting, but ultimately fruitless chase scene. And later, after identifying the kidnapper himself, David is shut down by the police and offered no support to track the criminal down. This final failure by the police leads David and Paul to successfully hunt the kidnapper themselves.

In a film that focuses on making the right choices, Highest 2 Lowest portrays the police as unethical, inept and inflexible. Spike Lee has never shied away from controversial depictions of police in his films, and more specifically from the violence of policing in America and the damage it has wrought on Black communities. Thankfully, Highest 2 Lowest doesn’t spend much time on the police themselves, but David understands that if a solution is to be found, he must do it himself. It’s a powerful juxtaposition from Kurosawa’s film (and a really fun 45 minutes as well), demonstrative of the ways that Black folks often cannot count on traditional means such as the police, to find justice. Interesting enough, the other deviation Lee made was that due to his own intervention, we see David end the film financially solvent unlike Gondo who, after leaving the investigation to the police force, is left financially ruined at the conclusion of High and Low.

Friendship, Fame & Funds: Shifting Thematic Anchors

I’ve already discussed how Lee elevates friendship as a moral signifier of strength. We see this in both David and Paul, but also with their sons, Trey and Kyle. In both friendships the men look after each other, offering emotional fortitude, advocacy, loyalty and commitment. This is significant as we understand them to be good men who make good choices. Additionally, it’s always beautiful to see powerful, poignant depictions of Black male friendship on screen.

Lee’s shift in how social capital is used in his film is an interesting one especially in place of the more obvious class commentary of the original. In Kurosawa’s film, Gondo’s wealth is a source of obsessive anger in his criminal antagonist, Takeuchi, and a source of initial derision from the police handling the case with explicit language connecting wealth to poor morals. In Lee’s film however, there is no meaningful judgement made about David’s wealth: he is unequivocally seen as the morally upstanding victim. It’s perhaps an interesting perspective for a Black American writer-director to have. On one hand, economic disparity in America is at a historic high which often lends itself to a portrayal of the wealthy as inherently evil, a la HBO’s recent show repertoire. (I miss you Succession.) On the other hand, the Black American wealth gap persists and representations of Black American wealth in media remain rare; we can, once again, look to HBO’s recent show repertoire. I wonder if Lee felt disinterest in positing Black wealth in any negative light; it’s certainly an editorial conundrum in a world where we know representation does matter.

In place of class commentary, Lee plugs in a modernized use of social capital via social media as opposed to the newspapers in the original. Like Gondo, David is praised in the media for his upstanding choice to pay the ransom for another’s child, but unlike Gondo, David receives real-time tangible benefits: his label’s music becomes popular again which leads to profit for his company. There is also a spectacular conversation between David and his son Trey about the likely long-term impact of their choice: social media and the internet mean a person can become much more (in)famous much faster and for much longer than in the past. Trey implores his father to consider that whatever choice he makes will likely follow the family for years to come. The press is part of Kurosawa’s film, specifically partnering with the police force to help the investigation continue. Ultimately though, even the press’ positive coverage of Gondo fails to insulate his family from financial devastation. Lee elevates the power of social perception as a tangible lever in his narrative.

Kurosawa’s film is a striking visual and metaphorical examination of class: from the title which translates more closely to “heaven and hell” in Japanese and the film’s narrative blocking that masterfully plays with height, to the socio-economic disparity between the two leads and the even greater distance between their moral standings. It is a strong thematic anchor that invites reflection. Lee uses social capital in a similar manner, allowing the longevity of public opinion and the hypervisibility of social media to give the characters cause to pause and reflect on their decisions.

A Developed Villain with a Dreamy Representation

To my great surprise, Rakim Mayers, known in the music world as A$AP Rocky, holds his own against acting titan Denzel Washington. Lee gave us two versions of Kurosawa’s famous face off scene, and both of them effectively flesh out the kidnapper in a way that adds depth to the film. The first face off in Highest 2 Lowest takes place at a recording studio with Mayers’ character, Yung Felon, inside the audio booth explaining with self-righteous satisfaction why he’s pleased to have successfully stolen from David. We’ve just left Yung Felon’s home where we met his partner and young child; as an audience, we’re sitting with the very real implications of Yung Felon’s actions—he has a family to support. It is a timeless excuse, and a compelling rationale for the criminal’s actions. In the recording studio, Lee makes great use of dialogue and the glass itself to emphasize the similarities and differences between the two men: both have families and big dreams but are separated by disparate opinions of how to protect those families and pursue those dreams. The dialogue between the two is fast-paced with the camera jumping from man to man like a tennis match. They banter about music, storytelling and values before chaos erupts. The second face off takes place after Yung Felon’s sentencing and begins with a short but compelling dream sequence wherein Yung Felon performs one of his rap songs with dancing women behind him and red and blue lights flashing on them intermittently. David watches in growing amused entertainment, nodding along in appreciation of the bars. Back in reality, Yung Felon sits across from David: detained yet determined.

Unlike in Kurosawa’s film where the kidnapping protagonist, medical intern Ginjirô Takeuchi, gleefully berates Gondo for his wealth and inattention to the suffering of others. In Lee’s adaptation, Yung Felon sedately and arrogantly speaks to David about influence and money, entreating him to grant Yung Felon’s biggest wish: being signed to David’s record label. Like Takeuchi, Yung Felon’s conversation ends with a big display of unhinged anger towards David. I was very curious to see how both Lee and Mayers would approach the iconic ending of this scene. It’s a credit to the movie that Lee kept the direction intact, and Mayers’ grandiose, vicious performance honors Tsutomu Yamazaki well. While the films deal with different themes, this scene with the maniacal criminal facing the calm, righteous victim felt critical and apt. Of course, Lee throws another manner of reinvention into his film with an additional scene after the final face off unlike Kurosawa’s film which ends there. Lee’s final scene is a touching and inspirational family moment that leaves the film once again celebrating David’s strength of character.

Yung Felon maintains the vicious anger of Takeuchi, willing to sacrifice his own life as well as others’ to achieve his aims. Yung Felon also maintains the moral cloudiness of Takeuchi: his actions fail to align with his aims, and the inconsistency ultimately leads to his demise. Unlike Takeuchi though, Yung Felon’s story is more concretely conceived, providing the audience a clearer window into his psyche and motivations. I’m a viewer who appreciates a great villain. Where Takeuchi is creepy but incoherent, Yung Felon breathes new life into the narrative as a bolder and more focused antagonist.

Does Spike Lee’s reimagining hold up to Akira Kurosawa’s original? Drop a comment & let me know what you think!